I was born in 1953, the year the Korean War ended. The Korean War was the most tragic event in the history of that ancient nation, but it would be almost sixty years before I learned this. In the rare event that the Korean War is mentioned in America, it is usually referred to as “The Forgotten War,” but a more accurate term would be “The Totally Unknown War.” Growing up, I never heard a word about it in school, never saw a television program or came across a book or a newspaper article about it, and even in college, where I was a history major, it wasn’t brought up once. Before going to North Korea in 2013, a few months short of my sixtieth birthday, I took a book about the Korean War out of the library and did some research on the internet. Prior to that, I could not tell you anything about military operations, civilian casualties, or how many American soldiers died in that conflict. About all I knew was that it ended in a stalemate.

In fact, until I was fourteen, I couldn’t tell you the first thing about Korea, North or South, other than that I’d seen it on a globe. When I was young, the implacable hostility of North Korea towards the U.S., a consequence of the Korean War, was totally overshadowed by the same level of anti-American hostility coming out of China. China, at that time, was as secretive and forbidden as North Korea is today, and as totalitarian as well, but its colossal size and huge population gave it a much more formidable image. I recall the front cover photograph of a textbook about Asia we were assigned to read in high school, which showed Chinese students with raised fists shouting and denouncing U.S. imperialism. There was pure hatred in those faces. That was 1967 and the Vietnam War was heating up. Bad things were happening in that part of the world.

On January 23, 1968, the U.S. naval ship Pueblo was captured by the North Korean Navy while fifteen miles off the coast of that country. I still remember first hearing about it – right after getting out of band practice as a high school freshman. That was my first inkling of the evil of North Korea. It was not a happy day. It seemed like we had nothing but enemies in Asia. One sailor was killed and several wounded when the Pueblo was attacked. The ship was captured and the crew of 83 taken to North Korea. After a few weeks of intense news coverage, they were pretty much forgotten as the Vietnam War reached the peak of its intensity in 1968, not to mention the anti-war protests, assassinations and race riots that swept the nation that year. After being held prisoner for eleven months, and often beaten to force them to admit they were spying (which they were), they were released. The commander of the Pueblo, Lloyd Bucher, wrote a riveting book about the ordeal which I read many years later.

In February 1972, President Richard Nixon stunned America and the rest of the world by visiting China and sitting down for a dialogue with that country’s aging dictator Mao Tse-tung, which we all saw on TV. A gradual thaw in Chinese-American relations followed, and within a decade normal trade and diplomatic connections were established, and the first American tourists arrived in a country that for so long had been on the dark side of the moon. This, however, hardly brought any peace to Asia. Our ally South Vietnam fell to the North in April 1975, and that same month a reign of terror began next door in Cambodia when the genocidal Khmer Rouge seized power, and in four years murdered twenty percent of that country’s population.

In the midst of these tumultuous events, in August 1976, a violent incident took place in the tense demilitarized zone that separates North and South Korea. Two American soldiers were pruning a tree for a clearer view to the north, when a squad of North Korean troops pulled up in a truck. An argument broke out, and ended with the two Americans being bludgeoned to death. I saw a brief segment about the incident on the television news, which showed the North Korean killers being greeted as heroes by their comrades. At the time, I was a staunch conservative who believed that America was a beacon of freedom in the world, that we were the good guys who could do no wrong, and if there was one country that was the exact opposite of everything America stood for, it was North Korea. A college friend of mine, who went into the Navy right after graduation, shared my sentiments. He had seen the same news clip on TV, and we had a good laugh at the behavior of these subhuman North Koreans. How smugly satisfied and superior we felt looking down at these fanatical Oriental savages.

Thirty-seven years later I had my picture taken with one.

In 1980 I visited South Korea, and while in Seoul, the capital, joined a bus tour with five or six other people to the DMZ which, far from being demilitarized, is the most heavily mined and hostile border on earth. Upon arrival we were met by an American soldier who served as our tour guide. Each of us had to sign a statement releasing the U.S. Army from any liability should something unfortunate happen to us. Our guide warned us not to make any gestures that would appear to be suspicious, as we would be observed from the other side, which heightened the sense of danger. And indeed we were observed: in the distance I could make out two North Korean soldiers watching us through binoculars. To actually be peering into the world’s most sealed-off, unknown and America-hating country filled me with awe. As a special treat, we were taken inside one of the empty military huts that straddle the line separating the Koreas, and where talks are held on rare occasions between North and South. The microphone wire on the conference table was the exact border. We were allowed to walk around to the north side of the table so that we could truthfully say we had been to North Korea!

Visiting the DMZ from the north side in 2013. The demarcation line runs through the middle of these huts. The large building in the background is in South Korea.

For quite some time after this experience, I heard very little about North Korea, but everything I did hear was negative. “The Hermit Kingdom” it was called, a country which, it seemed, no one ever entered and no one ever left – and no one had any idea what was happening there. North Korea might as well have been on another planet. Of course that only made it more alluring whenever I thought about the place. This same time slot, the 1980s, was when I did most of my traveling, going abroad almost every year for two or three months. It was also a time when I read a great deal and began to question much of what I had believed while growing up.

Among the educational benefits of travel is not only seeing with one’s own eyes, as opposed to the television screen, what the outside world is really like, but learning what other people think about your own country. For a long time I believed that the whole world looked up to America, and I considered myself very fortunate to have been born here. So strong was my patriotism, that the first time I traveled to Europe, in 1978, I sewed a small American flag on my backpack, because I wanted the whole world to know where I was from. This, however, did not bring any compliments, only a few sneers from Europeans of various nationalities with whom I’d struck up conversations while traveling by train. What I was usually told, in polite terms, was “You should get rid of that thing. Nobody wants to look at that.” This hurt and confused me; it was the beginning of a long and painful education. I was beginning to learn that, not only was America not admired throughout the world, but that my country was widely despised as an out of control, warmongering bully and its citizens scorned as hopelessly shallow and ignorant.

I’ve always been a voracious reader, intent on getting to the truth of things, with a keen interest in history and current events. The Vietnam War raged all through my formative years; it was a conflict that absorbed me emotionally, as so many of the men who fought and died there were just a few years older than me. Had I been born three years earlier, I likely would have been drafted and sent to war myself. Around the time I began traveling abroad, I read a wonderful book, A Rumor of War, by Philip Caputo, a Marine lieutenant with the first combat unit deployed to Vietnam in 1965. I was barely twelve when I realized a war was being fought in that faraway country, and from the start I was a passionate supporter of our men in uniform and of our participation in that conflict, believing it to be a righteous cause. I was sold on the “domino theory,” the popular idea that if we didn’t protect our South Vietnamese ally from the communist North, all the countries of Southeast Asia would fall one by one to the cancer of international communism. Even after we lost the war in 1975, I continued to believe that we had done the right thing by wiping out those evil Viet Cong guerillas and taking the war to the North Vietnamese, mining their harbors and bombing their cities. A Rumor of War made me aware that I had absolutely no idea of what had been happening on the ground while I was busy “supporting our troops” – no idea of the grim, everyday realities our soldiers were facing, and that from the earliest days the Vietnam War was a lost cause and a total fraud.

I read four other books about the war, three of them by American combat veterans, all of them reinforcing what Caputo had written about. One of them, Born on the Fourth Of July, hit home because the author, Ron Kovic, paralyzed for life when an enemy bullet smashed into his spine, had grown up in Massapequa, one mile from where I lived. The same themes recur in these and other books, and on the websites where Vietnam veterans have contributed their thoughts: how the military had exploited their love of country and sense of duty; the deaths of comrades that will forever haunt them; the pointless jungle patrols and assaults on obscure hills where so many men died for nothing; the suffering and accidental killings of civilians that still torment them; the murderous hatred, not of the enemy they were fighting, but of their own superiors, issuing senseless orders from the safety of their distant headquarters; being treated like dirt or even accused of being “baby killers” after returning home.

Of all the outrages – and I’m not even touching upon what was done to the land and people of Vietnam – none surpassed what I read on page 22 of a little-known book titled Compromised, by Terry Reed, a fighter pilot who flew numerous missions in the war. Reed recounted a meeting in 1970 during which a captain told he and his fellow pilots that there had been a policy change in Washington, and that areas where POW camps were located, previously off limits, were now to be bombed. When a brief mutiny ensued, a colonel came in and told the horrified airmen that if they did not follow their orders immediately, they were headed straight to Fort Leavenworth, and that another squadron standing by in Hawaii would follow orders.

That’s right: American pilots were ordered to drop bombs on American prisoners of war. And they did.

I know that most of you reading these lines were too young to remember the events I’m writing about, or were born after the end of that era. But personally speaking, the Vietnam War deeply affected my emotions as a teenager, and even more so in later years after I learned the suppressed truth about it. Many years ago I vowed to make a pilgrimage someday to this country and visit some of the places where so many young American men of my generation died. This I did, just a few weeks before I went to North Korea.

VIDEO: One of the most ferocious 10-day battles of the Vietnam War took place on Hamburger Hill, so-named because it was a human meat grinder. The Hill is in a remote, seldom-visited area close to the border of Laos. To climb it, I had to obtain a special permit and go up with a local guide.

Where, then, does that leave us with that nation? Well, you can imagine how a government that treats its own soldiers like used paper towels, treats the populations of countries it is at war with. From 1950 to 1953 the United States Air Force obliterated North Korea. In the history of warfare, it would be difficult to find another country that suffered destruction and loss of life on the same scale as that country did during “The Forgotten War.” In a nutshell, we used North Korea as a testing ground for napalm, which is jellied gasoline, and at the time a recent invention. Imagine filling all of our thirty major league baseball stadiums to capacity with innocent men, women and children, drenching them with gasoline, then tossing a lit match on them. Or to offer another analogy, picture the death and destruction of the September 11 terror attacks repeated every single day for two straight years – this in a country smaller in size than Alabama. That gives you an idea of what we did to those people over the course of three years – not to mention all the North Korean ground troops slaughtered from the air. In addition, our airmen flattened literally every town and city in that country by conventional bombing. By late 1952 there was nothing left to bomb.

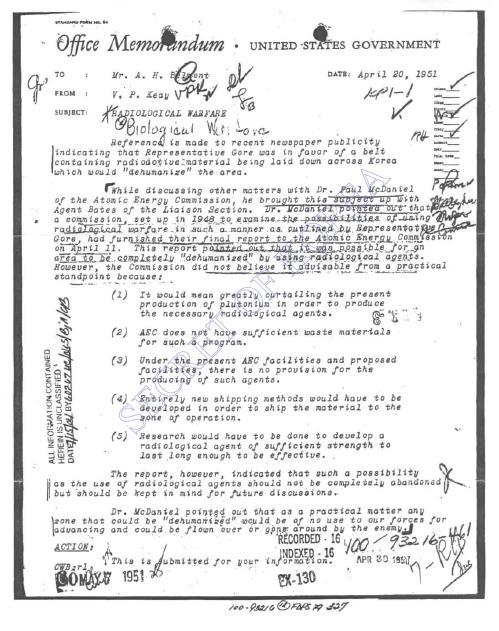

Nor is that all. I was amazed to discover that early in the war, which began when the north invaded the south, prompting President Harry Truman to get this country involved in what he called a “police action” – a police action in which, ultimately, some 36,000 American serviceman died – Truman, along with his top generals, repeatedly threatened the use of atomic warfare. This never came to pass, but the bombs were ready and our pilots were “waiting for the word,” while Tennessee congressman Albert Gore Sr. – father of the former vice president – actually proposed dropping so many atom bombs on the north so as to create a deadly radioactive belt lasting 60 to 120 years, cutting the country in half and preventing future invasions. This is not propaganda coming out of Pyongyang. It’s chronicled in U.S. Army archives and other publications pertaining to the Korean War. It was openly admitted by Air Force General Curtis LeMay, of Tokyo firebombing fame in World War Two, who commanded the air war in Korea. The facts can easily be referenced on the internet (see, for example, hnn.us/article/9245). No one disputes that these things happened, that we wiped out more than twenty percent of the population of North Korea (some believe the real figure is closer to thirty percent). The only uncertainty, which will never be resolved, is the precise number of victims, and the proportion incinerated by napalm, buried under rubble, or succumbed to disease, starvation or exposure. The parents or grandparents of virtually every North Korean alive today either died or lost everything they had in “The Forgotten War.” The question is, why is not one in a thousand Americans aware of this? Why is it never mentioned in the media here? Does it not go a long way in explaining North Korea’s chronic hostility towards the U.S. government and military – especially in light of the fact that our armed forces never left the Korean peninsula, and 28,000 U.S. soldiers are still stationed in the south?

But here’s the most amazing fact of all about this country, which I learned several months after my visit: North Korea is an American creation! If you’re in your late fifties or older, you might recall the name Dean Rusk, who served as secretary of state in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. During World War Two, Rusk was an obscure, high-ranking noncombatant stationed in the Far East. By chance, he was given the assignment of figuring out “what to do” with Korea in the power vacuum created by Japan’s defeat and withdrawal from that country which it had occupied since 1910. He tells us that the Department of State and a section of the military bureaucracy known as SWINK (State/War/Navy Coordinating Committee) could not agree on a solution. In his own words, as they appear on page 124 of his memoirs As I Saw It, this is what happened:

We finally reached a compromise that would keep at least some U.S. forces on the Asian mainland, a sort of toehold on the Korean peninsula for symbolic purposes. During a SWINK meeting on August 14, 1945, the same day of the Japanese surrender, Colonel Charles Bonesteel and I retired to an adjacent room late at night and studied intently a map of the Korean peninsula. Working in haste and under great pressure, we had a formidable task: to pick a zone for the American occupation. Neither Tic nor I was a Korea expert, but it seemed to us that Seoul, the capital, should be in the American sector. We also knew that the U.S. Army opposed an extensive area of occupation. Using a National Geographic map, we looked just north of Seoul for a convenient dividing line but could not find a natural geographical line. We saw instead the thirty-eighth parallel and decided to recommend that. SWINK accepted it without too much haggling, and surprisingly, so did the Soviets…. SWINK’S choice of the thirty-eighth parallel, recommended by two tired colonels working late at night, proved fateful.

That’s right, Joseph Stalin, our ally turned enemy, history’s greatest mass murderer behind Mao Tse-Tung, installed his point man Kim Il-Sung, grandfather of North Korea’s current dictator Kim Jong-Un, to rule over the northern half of a country that had never before been divided and whose people had absolutely no say in the matter. And this was done on the whim of a couple of ignorant, exhausted military bureaucrats who had glanced at a map of Korea in National Geographic!!

Truth is indeed stranger than fiction — especially historical truth.

It’s time for a reality check, my fellow Americans – time to put the facts in their proper perspective:

• North Korea “has a problem” with only three countries in the world: the U.S., for all the reasons I’ve just mentioned; South Korea, which it regards as a “puppet state” for allowing a large American military presence there; and Japan, for its brutal occupation of Korea in the first half of the twentieth century, along with the proximity of American air bases in that country.

• The U.S., the only country ever to use atomic weapons, has a stockpile of 7315 nuclear warheads; North Korea has less than 10.

• We exterminated millions of people who weren’t bothering us and posed not the slightest threat to us, in North Korea, a country halfway around the world. North Korea has never harmed any innocent American civilians anywhere, and has never attacked another country anywhere in the world, other than its southern neighbor in the Korean War.

• North Korea is on good terms and has diplomatic relations with many countries throughout Africa, Asia and Europe, including Great Britain, Germany and Sweden. I have personally spoken to people from various European and Asian countries about North Korea, and while most of them consider it a very odd place, and not somewhere they would want to live, none characterized it as a danger or threat to anyone. How strange that Americans, citizens of the world’s most powerful and aggressive nation, are the only ones who seem to feel that way.

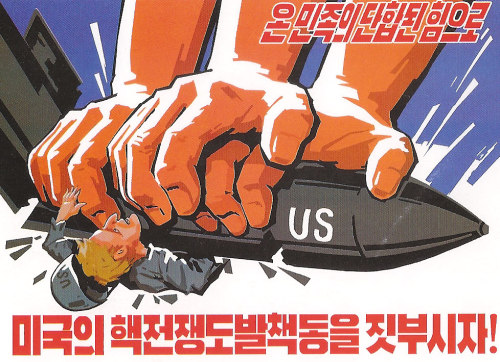

• It is true that in the spring of 2013, the North Koreans posted some viciously anti-American videos on the internet, including one threatening to turn Washington D.C. into “a sea of flames.” (What the media did not report, however, was that this was a reaction to our Air Force flying Stealth bombers over the Korean peninsula in menacing fashion, obviously to rattle their nerves.) It is also true that North Korea is an extremely militarized country. Everything I saw with my own eyes while there, however, pointed to a fanatically defensive, not offensive, mindset – always, always with remembrance of the Korean War and the message “Never Again!” (Among the many eerie sights in the country, which one sees with increasing frequency while getting closer to the DMZ, are concrete columns along the wide, deserted highway, erected so that they can instantly be toppled to block a tank assault from the south.)

• With Stalin’s support Kim Il-Sung did attempt to subjugate South Korea by invading in 1950, but the world is a completely different place today. For many reasons there is no way his grandson, Kim Jong-Un, would order an invasion of the south. (If he did, his soldiers would probably throw down their weapons and embrace their “enemies” as brothers.) And even if he wanted to invade, North Korea is very much under the thumb of China, and the Chinese would never tolerate such an incursion, since it would disrupt their thriving trade with South Korea. And beside all these points, there is no sane reason for Americans to concern themselves with whatever happens in Korea.

Having said all this, I would not deny for a moment that the people of North Korea live under one of the most oppressive regimes on earth, if not the most oppressive. I make no apologies for the dysfunctional policies of that government which imposes such a harsh burden on its people. Nor do I doubt that a large number of real or suspected dissidents, said to be about 150,000, languish in labor camps scattered throughout the country. (It must also be said, however, that one should be skeptical about the many lurid tales about the country. A recent one, first published in a Singapore newspaper, claimed that Kim Jong-Un had his uncle and five aides stripped naked, thrown in an iron cage, and fed to 120 starving hounds; “quan jue,” or execution by dog, it was called. The writer later admitted that he made the whole thing up.) An excellent book on the bleak nature of everyday life in North Korea, written by a rare journalist who reports the facts honestly and responsibly, is Nothing To Envy, by Barbara Demick.

However, judging from the significant reforms and in many cases the total collapse of communist systems around the world, I think it’s just a matter of time before the leaders of North Korea ease up on their long-suffering people. In fact, there are signs in the last few years that a slight “mellowing” has been taking place. Certainly, there is a deep yearning among all Koreans, north and south, for their country to be reunified. It is a yearning embodied in a huge statue of two women, one standing on each side of a road leading out of Pyongyang, holding aloft a portrait of a single Korea — an admirable nation of one people, one culture, one language so cruelly and unnaturally ripped in half by our own government. No one knows how it will happen, and it won’t be easy, but someday, somehow, this country will be reunified, just as it happened in Germany and in Vietnam.

And speaking of Vietnam, I never would have imagined, forty years ago when the south fell to the north, and during the two decades of festering hatred and bitterness that followed, that eventually we would put all those toxic feelings behind us and become friends. Yet that’s exactly what happened – not only in diplomacy, trade and tourism, but with thousands of our combat veterans who have returned to Vietnam to heal the wounds of war and get to know their former enemies, in the process learning that they’re “regular guys” just like themselves. Videos of these reunions, some of which are quite emotional, can easily be found on the internet, and we all know in our hearts that this is a good thing, this is the way it should be.

Unfortunately, no such conciliation ever came out of the Korean War. Yet after traveling there, I felt inspired to do my part in helping to bring the people of our countries closer. As we returned from our unforgettable visit to the DMZ, I said to Chris, our American tour leader, “You know, all our guys have to do is walk across the border, sit down with a bunch of North Korean soldiers over a couple of beers, and in ten minutes they’d be the best of friends.” He totally agreed, and even though I’m not naive enough to think that’s going to happen anytime soon, there’s nothing to prevent it except our monolithic military bureaucracy which has a vested interest in keeping the Korean pot boiling forever. And I wouldn’t be surprised if every one of our troops in South Korea is as brainwashed about those “fanatical savages” to the north as I once was.

In a land of unexpected quirks, one of the quirkiest is the genuine affection North Koreans have for American tourists, while at the same time detesting the U.S. military machine. The postcards above may seem like the height of psychotic belligerence until you learn what our B-52 bombers unleashed on that country during the Korean War.

I know I can’t change the world. But I can do my own small part. The bottom line is that North Korea has offered the hand of friendship to Americans of good will, and I hope to find a few with the independence of mind, generosity of heart, and spirit of adventure to grasp it.